Researchers return to the Farm Hub to study the connection between grassland songbirds and agriculture

Noah Perlut and a field crew of students recently returned to the Hudson Valley Farm Hub to continue their Bobolink study. One morning in early June they arrived at twilight carrying mist nets and cloth bags to catch Bobolinks and Savannah Sparrows. It was a good day to capture Bobolinks—the temperature moderate for an early summer day with low winds. Over the course of the morning the team captured and banded 17 Bobolinks, 5 Savannah Sparrows and 3 Song Sparrows.

In 2021 Perlut, a professor at the University of New England in Maine, started the study at the Farm Hub with the goal of understanding the local movements and migration of grassland songbirds, particularly Bobolinks. How similar will Bobolink movement patterns be as compared to a population in Vermont that Perlut has studied since 2002? Do Bobolinks visit other nearby grassland patches surrounding the Farm Hub? If so, how far will they travel?

Over the past 21 years, Perlut has banded ~10,000 Bobolinks and Savannah Sparrows, most at Shelburne Farms in Vermont. This project aims to compare the Vermont population—which is in a large, grass-based agricultural landscape where the birds have occupied these fields for generations—with the Farm Hub—a relatively isolated agricultural landscape, where these birds were recently restored.

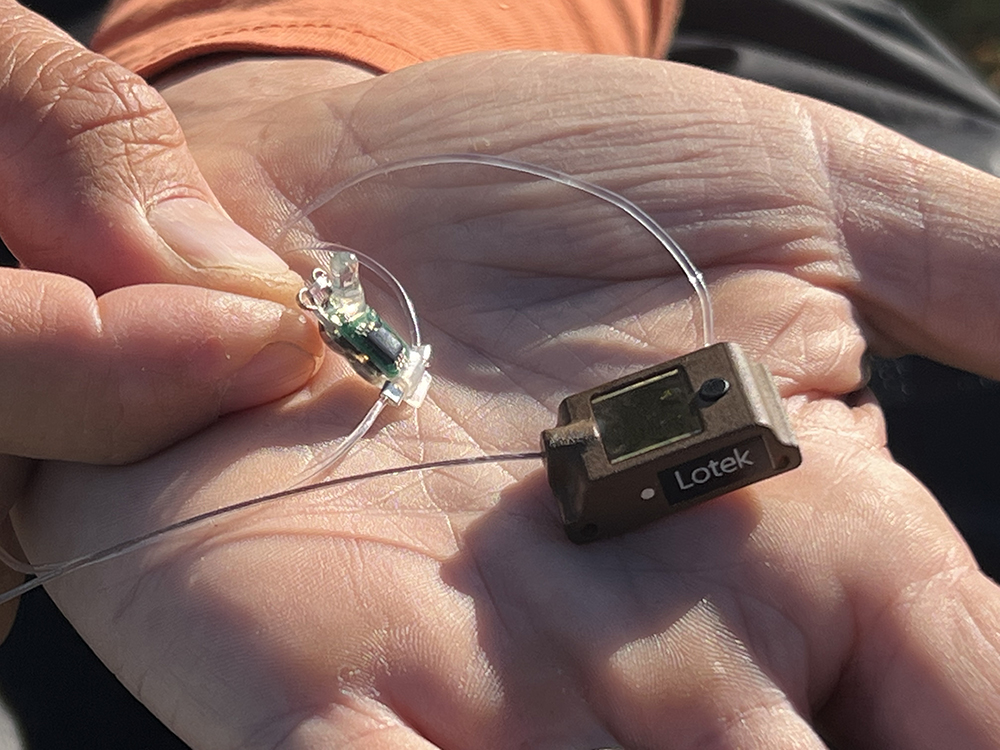

Technological innovation has shaped this research. Perlut uses geolocators and satellite tags to track the birds. The data is stored in the devices (geolocators) and the birds must be recaptured the following year, or he is able to see some birds’ movement in real time. Perlut has some colorful stories when it comes to the Bobolinks tracked from last summer.

One Bobolink flew from the Farm Hub to the Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge in Maryland, and then from Maryland to Cuba nonstop. After three days in bean and plantain fields in Cuba he flew nonstop to Colombia.

Perlut’s passion and fascination with these birds remain as strong as when he first started over two decades ago. While Bobolinks are tiny, most of them weighing as much as two strawberries, they fly great distances in search of food; their journeys begin in the northeastern U.S. and Canada in early fall, where they head to Venezuela for a month, fly over the Amazon and land in Bolivia for a month, and then disperse to Argentina and Paraguay for the remainder of winter. They can live for at least 11 years. Unfortunately, Bobolinks as with grassland species overall, are on the decline in part due to habitat loss.

We recently caught up with Perlut at the Farm Hub after he finished banding the birds.

Explain why is this research significant? What are you trying to do by tracking Bobolinks on farms?

The Farm Hub asked me to come here to understand more about the population that is breeding here. It’s a new population. It didn’t exist here before 2016 when this was a row-crop field and these birds are declining throughout their distribution. They are declining by at least 3% a year since the 1960s.

The Farm Hub is contributing to species restoration by maintaining this habitat.

Today we banded nestlings from four nests, including twelve chicks—there are at least 13 nests and let’s say if half of those nests are successful, that is fantastic news. That the Farm Hub will have not only provided habitat for adults to survive, but also produce maybe 40 or so chicks across the summer is noteworthy.

What were some of the highlights of your research at the Farm Hub?

We know that there are at least 13 female Bobolinks here this year and that is great news. We have already found four nests with chicks that are leaving the nest in the next couple of days. So that is also great news. We banded all those chicks. We deployed tracking devices on every adult Bobolink that we caught (17), which is super exciting. And we have seen one bird who we know was banded here last summer as a chick so that is super exciting to see that he’s come back to breed—a sign that these birds view the Farm Hub as high-quality habitat.

Were you surprised at that?

A little bit. They return to where they were hatched in Vermont, but it is not been known for other populations and so we only banded 14 chicks here last year…Only about six or seven of them will survive the first full year. So, one out of six have really come back here to nest, which is great. The others have likely dispersed across the region.

What’s different this year for your research, compared to last year, or maybe what’s the continuation?

This is a continuation. This year I think we are having more success trapping Bobolinks. Every one of them is getting tracking devices, that is also really exciting so hopefully next year we can come back and remove these tracking devices and see where they have been and understand how this compares to other populations that we have tracked.

Why is so exciting that each one of them now has a tracking device?

That’s kind of the gold standard, right? To be able to mark every single bird in your population and be able to follow them throughout their year is what everybody is aiming for. We can then link what we know happens to them on the breeding grounds with where they go when they leave the Farm Hub. And the good news is that this population is so isolated geographically and also on this farm… They are congested into this one field that we can really do a good job of knowing how many of them we have banded and how many of us are tracking.

You shared the story about one of the Bobolinks that flew from Maryland to Cuba. Why is that significant?

(It is significant) for a couple of reasons. One is the type of tracking device that we used on that bird, and we have deployed three more here today, which gives us an incredible level of detail of exactly where the bird is and exactly when it moves.

That bird went south to a place called the Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge on the southern end of the Delmarva Peninsula. And interestingly enough, 25% of the birds that we tagged with a different kind of tag, in Maine, Vermont, and Pennsylvania also went to this same place (nanotags). It really gives us a huge amount of information relative to migration stopover sites, and how important it is for that area to be thinking about Bobolink conservation.

From Blackwater, this male then spent three days in Cuba and flew non-stop to Columbia, which is just a remarkable story to think about a bird that weighs as much as two strawberries and can stay in the air and flap its wings for two straight days…. insane. And then eventually make its way down to Argentina. And so, we are stewarding the genetics and behavior that result in this spectacular migration. The Farm Hub talks a lot about being stewards of the property, and what does it mean to be a steward in agriculture? Biodiversity is one of the things that the Farm Hub is a steward of—and I am so happy to see the farm taking this wholistic commitment seriously.

Finally, why Bobolinks?

Por naturaleza, son sencillamente espectaculares. Volverás caminando hasta el granero y probablemente sentirás "Oh, mis pies me están matando". Eso es sólo a quarter of a mile. These Bobolinks are going to fly 7,000 miles to Argentina—each way. That is just absolutely remarkable. The other reason is that these birds have become linked to agriculture everywhere they go. Whether that is here in New York, whether it is in Maryland, Venezuela, Argentina, Colombia, or Bolivia, they are using agricultural areas, and so their future is tied to our stewardship of agriculture.

To learn more about Noah Perlut’s research click aquí.

-Amy Wu

Featured image of Bobolink on newsfeed courtesy of Bob Miller