Violet Wu

Searching for Bobolinks: A young researcher pursues her passion for a migratory songbird and conservation

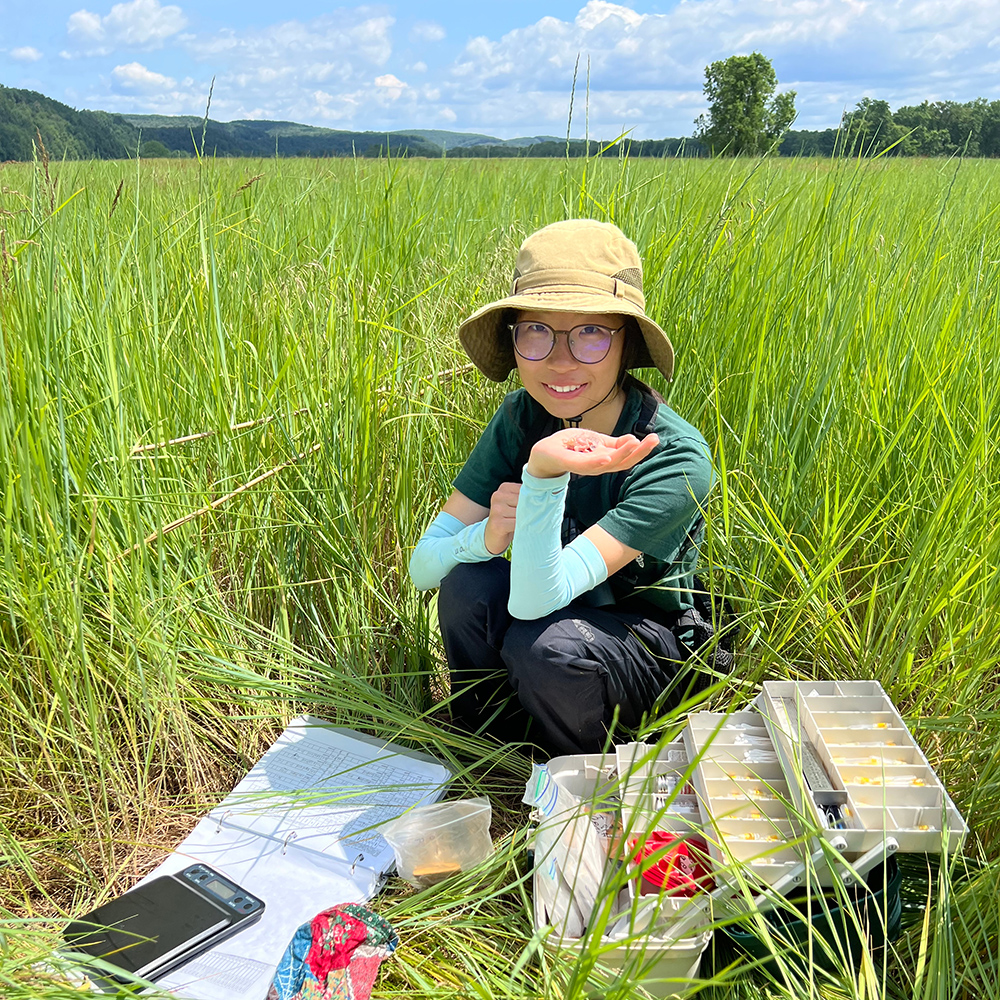

Violet Wu

Graduate Student, University of New England

At dawn the sun begins surfacing behind the farm fields. The air is heavy with mist amid a backdrop of a sorbet-colored sky — maroon, fiery orange, purple haze. This is the magic hour, the time just before sunrise — a prime window not only for the beauty of the seasonal landscape but also for birds.

Amid a sea of tall green grass, there is a rustle. A young woman with binoculars around her neck and a bamboo stick in her hand emerges from the grass. On this July day it is just shy of 5:30a.m. and Violet Wu is hard at work searching for Bobolinks, a migratory songbird known for its propensity to nest in hayfields as well as its ability to fly long distances to winter in South America.

Since 2023, Wu has been researching and studying Bobolinks under the guidance of her advisor Noah Perlut, a professor at the University of New England who leads the Perlut Lab. The lab explores how human habitat management effects the ecology and evolution of diverse species and diverse habitats. Perlut, a member of the Farm Hub’s Applied Farmscape Ecology Research Collaborative (AFERC), began studying the Bobolink population at the farm in 2021. The goal of this study is to understand the local movements, nest success and migration of grassland songbirds and apply what is learned to wildlife conservation efforts. Grassland songbirds such as Bobolinks are declining significantly by at least 3% a year since the 1960s.

Look closely at nature. Every species is a masterpiece, exquisitely adapted to the particular environment in which it has survived. Who are we to destroy or even diminish biodiversity?

- E.O. Wilson

Left top, a Savannah Sparrow nest, left lower Wu shares about Bobolink research at the Farmscape Ecology Field Day in August 2024 and right, a male Bobolink is tracked with satellite tag at the Farm Hub. Select photos courtesy of Violet Wu.

While Wu is an avid birder with an interest in grassland birds, her real muse are Bobolinks, a unique interest that connects with her drive towards ecology and conservation. Bobolinks have a special place in her heart. She loves the way they look, especially male Bobolinks with their black feathers and iconic splash of color on top of their heads.

Other Bobolink factoids, the male and female also have distinct flight patterns and calls. They are also travelers and impressively fly some 12,500 miles to and from southern South America annually. In their lifetime these birds can circle the world 4 to 5 times.

“Bobolinks are an amazing species of bird. They nest on the ground in grasslands and are long-distance migrants who travel all the way to South America during the winter every year,” she says. “They are a species that are declining very fast, so it’s important to conserve them especially on farms where they nest because their nesting season coincides with farmers’ haying schedules.”

Growing up in Beijing, China, skyscrapers and buildings were a more common sight than green spaces. Her father was a software engineer and mother a teacher at an adult school. Since childhood she has loved animals, so she sought a career where she could connect with them.

“The only career I could think of that works with animals was being a vet,” she says. Her career aspirations led her to study animal science at the University of California, Davis with the goal of being a veterinarian. Then she discovered the wildlife, fish and conservation biology major, which seemed to combine her interest in the outdoors, nature and animals. At Davis she worked as an undergraduate research assistant and connected with seasoned birders.

“I love fieldwork more than clinical work, so I switched to wildlife conservation,” Wu says. In 2023 she earned her bachelor’s degree in wildlife conservation.

It wasn’t until the height of the pandemic in 2020 that she fell in love with birding. “I just love being in the field and getting to learn the calls, songs, and behavior of the birds,” she explains. “I switched my major to wildlife conservation and started bird watching during the pandemic. And I really fell in love with birds and want to conserve them better. So, I looked for bird-related jobs after graduating.”

Top left, Wu and Noah Perlut search for and band Bobolinks at the Farm Hub. Photos of Bobolinks courtesy of Violet Wu.

Wu applied for Perlut’s Bobolink program in part driven by an interest in the tracking technology. The Bobolinks are tracked using satellite tags or geolocators.

As part of the program Wu was trained at Shelburne Farm in Vermont (a base for Perlut’s research). This included learning about everything from observation techniques to bird calls. In 2023 she joined the University of New England as a master’s student through which she came to the Farm Hub to study the breeding and migration ecology of an isolated and newly established population of Bobolinks as part of Perlut’s Bobolink research project team.

Wu’s master’s thesis focuses on the movement patterns and habits of Bobolinks on farmland.

“The welfare of farmers and birds are almost always contradicting. Farmers want to harvest the crops as their best yield, but that coincide with the peak nesting time of Bobolinks in summer. Mowing destroys the bird nests in the field. Understanding the breeding ecology and timeline of the birds is important for designing the best solution to benefit both farmers and the birds,” she explains.

Wu ultimately hopes to use her research to help farmers tackle farming challenges and fuel conservation.

In 2024 she returned to the Farm Hub to search for Bobolinks for banding and tracking. Without knowing the exact reasons, it was a poor year for Bobolinks at the Farm Hub. Over the course of the summer, she caught only three—two males a female from the previous year.

When Bobolinks were not around, she shifted her focus to Meadowlarks and was elated to find nests. On one morning she parted the sea of green, and amid the soft bed of grasses she discovered a nest of baby Meadowlarks. She marveled at the nest. Finding nestlings is always a delight.

Outside of work, Wu’s hobbies relate to birding. She’s an avid filmmaker and photographer and documents her discoveries. Since 2021 she has filmed, edited or narrated wildlife documentaries and educational videos about insect physiology and ecology. Her channel on the Chinese social media platform BiliBili has nearly 110,000 subscribers and over 5 million views.

After graduating in spring 2025 she hopes to work as a bird ecology field technician as a start. What would her dream job be?

“I’d be a full-time birder just for fun or maybe for research too,” she smiles. “But if there were no money to be considered, I would want to travel to different countries and places to see their different birds.” And hopefully there will be some Bobolinks in the mix.

Q & A with Violet

Read the full interview with Wu.

Update: In September, Wu returned to the University of New England in Maine to complete her master’s degree and work at Noah Perlut’s lab. At the lab she analyzed the data collected from the geolocators and satellite tags from the birds at the Farm Hub and the Vermont farm. She compared the two populations and examined the birds’ long distance migration routes from the Northeast to South America and back. While the data analysis will be an important part of her master’s project, the ultimate hope is that it will be published and shared with fellow researchers, scientists, farmers, conservationists.

After finishing my undergraduate degree in Wildlife Conservation at University of California, Davis, I had the opportunity to join Dr. Noah Perlut’s lab as a new master’s degree student studying the breeding ecology of Bobolinks on the farm.

Bobolinks are an amazing species of bird. They nest on the ground in grassland and are long-distance migrants who travel all the way to South America during the winter every year. My advisor Noah has been studying their breeding ecology in Vermont for 22 years, and the work I’m doing on the farm will be a sister project focusing on the small population here. The Bobolink population that breeds on the farm is relatively newly established one (after Kernza are planted in Field #8) and very isolated compared to the bigger population in the Vermont site, so it is interesting to compare the ecology and behavior of the two populations. We catch the birds on the farm, band and measure them, collect blood samples, and put tracking devices on them. The tracking device will tell us about their daily movement on the farm and (hopefully) the route they will take during migration. We will also monitor the survival of their nests.

As a child I knew I like animals, and the only career I could think of that works with animals is being a vet, so I came to study animal science at UC Davis. Then I discovered the major Wildlife Conservation, and I found it much more interesting to me. I love fieldwork more than clinical work too, so I switch to Wildlife Conservation. I fell in love with birding during the start of the pandemic, and now it has become the most important part of my life! I grew up in a big city with not much green space left, so when I arrived in such a natural environment during my undergraduate years, I made connections with the wild animals immediately. Learning bird language and behavior is my favorite. Now after being an avid birder for three years, I chase rarities and make my own documentaries of them.

That we can use the newest technology and put on backpacks on the bobolinks and know their position through satellite signals. How amazing is that!

I’m mainly studying their movement and behavior, so I’ll be looking at how they use the landscape, how they use their resources. Being a fast-declining species, I would say the most important thing I learned from them might be that their habitat requirements might be more strict than what we thought. Because last year there were a dozen of them, and the breeding success was not good because predation rate is high in this field full of mice. So, this year they decided to not come here. They learned from breeding success previous years for deciding where to breed this year.

We need to provide high quality and long-lasting fields for them, because they rely on the stable breeding ground that they can return year after year. For example, last year a bird breed here, and the nest got eaten, so she knows, Oh, this is not a good ground, and then he needs to choose another ground, and it’s an energy expenditure for the birds to switch, to do a lot of those flying scouts to look for potential nesting grounds, but having a long-lasting and high quality ground that can be, the birds can breed there for years after years, might be helpful for their population.

Being not that powerful and strong in strength may mean it will take longer for me to set up a mist net than Noah for example. When multiple people are here doing the work together, we can just stick the metal pole deep in the ground that we use to stabilize our mist nets.. But I can’t do that myself. I have a heavy drill with me, and I will drill a hole first, then I can get the metal pole into the ground alone. I need to carry a drill to the field if I am going to catch a bird by myself. I drill a hole in the dirt and then stick the pole into the hole. I may not have as much physical strength, but there’s also a way I can do the same job.

Finding a nest. It’s always a great discovery and made me imagine that I revealed the hidden secret of this bird and no one on earth beside me and this bird know where his nest is , and it’s secretive and takes a lot of patience and work to locate the nest. Sometimes you can find it by luck, but most of the time for me, it takes a long time of observation. It’s really rewarding feeling when I find one.

If you’re lucky, you can flush a bird directly beneath your legs and it might be easy to locate. But if you are observing a bird, like going into the nest, and you only know a general area where the nest feed. You’ll need to sit there and watch for the birds coming in and out, in and out for many, many times and try to narrow the area and then you go, like, it usually takes a long time, maybe hours, one hour or two hours of waiting. I try to sit there, pay full attention on the bird, see where she lands. And in this, after she lands, you must stare at that grass for maybe 10 minutes or 20 minutes and sometimes a long time and wait for the birds to fly out again and you need to follow the birds to see where she lands. And it’s just a really long time of observation, so you can’t be distracted by other birds or other stuff, because when you look at another one and you don’t know if your previous bird has flown, then your previous work will be wasted. Patience is important. Even if you are not seeing anything in the field, you’re staring at the grass, you need to wait for the birds to come out again and not be disturbed by other stuff.

“Look closely at nature. Every species is a masterpiece, exquisitely adapted to the particular environment in which it has survived. Who are we to destroy or even diminish biodiversity?”

— E.O. Wilson

Resources

Learn more about Bobolink research at the Farm Hub and watch the short film The Wonder of the Bobolink.