Many little hammers for weed suppression during organic Kernza establishment

By Uriel Menalled, Chris Pelzer, and Matthew Ryan

The authors are researchers at Cornell University’s Sustainable Cropping Systems Lab, based in Ithaca, NY as part of Cornell. Lead author Matthew Ryan is an agroecologist who conducts research on sustainable cropping systems.

Intermediate wheatgrass (Thinopyrum intermedium) is an emerging perennial grain crop that has the potential to help transform agriculture. Intermediate wheatgrass is different than other grain crops because it is a perennial and can be planted once and then harvested for multiple years. Researchers atThe Land Institute in Salina, Kansas are leading efforts to domesticate Intermediate wheatgrass as a grain for human food and have developed improved lines, which are marketed as Kernza®.

Kernza has a nutty flavor and can be used as a whole grain like rice or milled into flour and used in bread and baked goods. Kernza is the first perennial grain crop to be incorporated into commercial products including cereal, crackers, and beer, garnering investments from General Mills and Patagonia Provisions.

Kernza can contribute to regenerative agriculture by reducing soil tillage and maintaining continuous soil cover, which can minimize erosion, store carbon, and build soil health. Despite these important benefits and strong consumer interest, Kernza adoption is constrained by low grain yields compared with annual crops.

Annual grain crops such as wheat (Triticum aestivum) have been improved over thousands of years by selecting genotypes with larger seeds and other desirable characteristics. Using the same approach, crop breeders working on Kernza are making rapid progress with increasing grain yields.

Managing weeds

However, research is also needed on management practices to optimize Kernza production. Previous research has shown that Kernza is particularly susceptible to weed competition during the establishment year, which can lead to poor stands and reduced grain yields. Farmers also expressed concerns about weeds in a survey, where “increased pest problems (weeds, disease, and insects)” was ranked the top concern about growing perennial grains among organic producers. This matches the results from our recent on-farm research with organic farmers in the Finger Lakes Region, where several reported that managing weeds was their biggest concern with perennial grains.

As part of a new partnership between the Hudson Valley Farm Hub and the Cornell Sustainable Cropping Systems Lab, we are growing Kernza and testing several ecological weed management practices that can be used in organic production. A key concept in ecological weed management is to use “many little hammers,” a term coined by Matt Liebman Professor of Agronomy at Iowa State University, and Eric Gallandt a professor at the University of Maine’s School of Food and Agriculture, that defines how adding more weed control tactics can have a combined powerful effect.

The idea of the many little hammers (citation 1) approach is that numerous cultural and mechanical weed management practices are minimally effective on their own; however, when they are used together as part of an integrated strategy, the combination of practices can be highly effective. Using multiple cultural and mechanical weed management practices can also reduce the burden of protection for any one practice, and result in synergistic interactions between practices.

Testing treatments

In spring 2020, we tested different weed management practices in Kernza that were seeded in fall 2019 at the Hudson Valley Farm Hub and Cornell University’s Mount Pleasant Research Farm in Ithaca, NY.

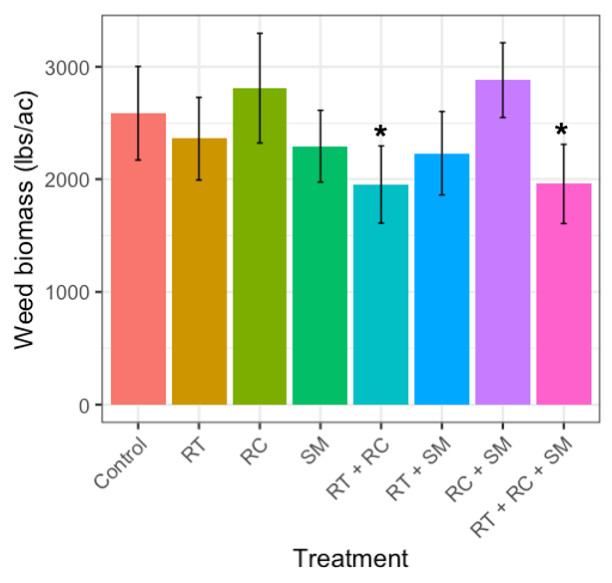

Three weed management treatments were compared: 1) rotary hoeing and tine weeding (RT); 2) red clover interseeding (RC); and 3) spring mowing (SM) (Figure 2). We also tested every combination of the treatments: RT + RC; RT + SM; RC + SM; and RT + RC + SM. Weed management practices were implemented between the first and third leaf stages in April and May. Red clover (Trifolium pratense) was broadcast seeded at 12 lbs/acre.

Prior to implementing any of the experimental treatments, Kernza fields were mowed at each site in early spring to suppress early emerging weeds that grew above the canopy of the Kernza seedlings. Kernza was harvested when its seed heads began to turn golden in late summer (August 19-20 at the Farm Hub and August 12-13 at Mount Pleasant). We sampled all weed and Kernza biomass within two 2.7 ft2 sampling areas randomly placed within each plot. All plants were cut at the soil surface, identified at the species level, dried, and weighed. By comparing weed suppression to an untreated control treatment, we were able to measure how each practice affected weed biomass and Kernza performance.

We hypothesized that combining all three weed management practices would result in the greatest weed suppression and grain yield of Kernza.

The effect of each management treatment was assessed by comparing the average weed biomass in each treatment to the control. At both sites, annual grasses were the dominant weeds across all treatments. Weed management practices had no statistically significant effect when implemented individually (Figure 3). However, a 24% reduction in weed biomass relative to the control treatment was observed when all three practices were combined in the RT + RC + SM treatment (P < 0.05), and a 25% reduction in weed biomass relative to the control treatment was observed in the RT + RC treatment (P < 0.10).

Our results illustrate the value of the many little hammers approach and provide insights about weed management that should be explored further. In particular, it appears that the weed suppressive effect of interseeding red clover was activated by the rotary hoeing and tine weeding. Although not effective at reducing weeds when implemented alone, the shallow soil disturbance from the mechanical weed management practices might have facilitated red clover establishment. In addition to weed suppression, intercropping with perennial legume forage crops, such as red clover, can provide nitrogen to Kernza through biological nitrogen fixation and increase forage quality in dual-purpose grain and forage crop production.

Next steps

More research is needed to better understand the effects of different ecological management practices on weed suppression, soil health, grain yield, and overall profitability in organic Kernza production. In our experiment, even though the combination of red clover interseeding with rotary hoeing and tine weeding reduced weeds, the level of weeds in the combined treatments was still high enough to reduce grain yield, especially at the Mount Pleasant site. Also, while the combination of weed management strategies provided the best weed suppression, increased labor and fuel costs need to be considered when developing management guidelines. Based on our on-farm research with organic Kernza production, it is clear that weed problems can be avoided by selecting fields that have low weed populations as well as using cover crops and a false seedbed to reduce perennial weeds and the soil weed seed bank prior to seeding Kernza. The next steps in our project are to analyze crop yield data and assess the profitability of each treatment. We will also be conducting new research on organic dual-purpose management as part of a USDA-funded project with collaborators in Ohio, Minnesota, and Kansas.

The above graph shows the average weed biomass in each treatment: spring mowing, red clover interseeding, and rotary hoe and tine weeding. The control did not receive any weed management. Data were pooled over both research sites. Error bars show the standard error, and asterisks (*) indicate that weed biomass was different than the control treatment. Graphic courtesy of Cornell Sustainable Cropping Systems Lab.

Citations

1 Liebman, M., Gallandt, E.R. and Jackson, L.E., 1997. Many little hammers: ecological management of crop-weed interactions. Ecology in agriculture, 1, pp.291-343.

Using “Many Little Hammers” to Combat Herbicide Resistance, by Bryan Brown, Ph.D. Integrated Weed Management Specialist, New York State Integrated Pest Management Program, Cornell University