Spanish translation below / traducción en español abajo

Tracking the migration and movements of grassland songbirds from Hudson Valley, NY to South America and back

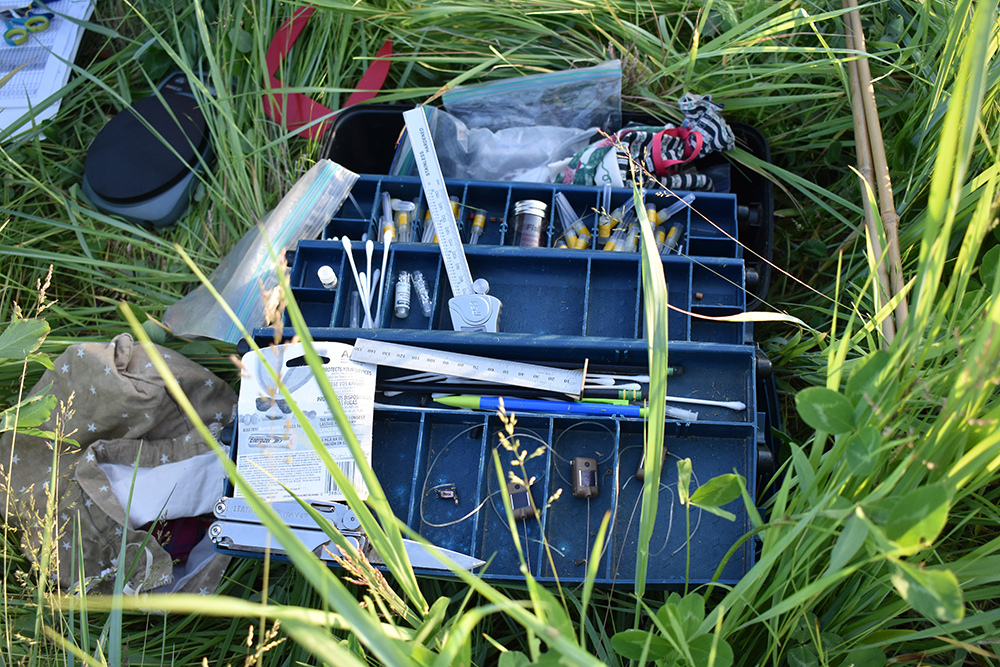

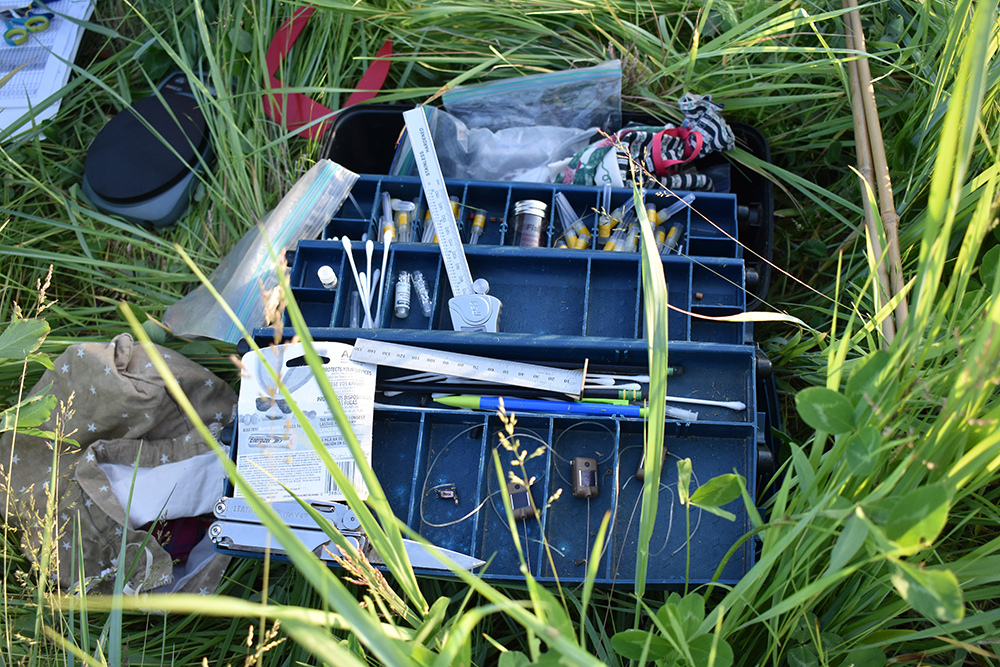

At twilight Noah Perlut and his undergraduate research assistants arrived at the farm. The crunch of their rubber field boots filled the cool air as they entered the tall grass. They carried a bevy of items–a toolbox packed with rulers, colored bands to put on birds’ legs, and thumbnail-sized satellite tags, along with mist nets and palm-sized cloth bags to hold birds. Hours before dawn they were already geared up to catch Bobolinks. This was early May.

The Bobolink research initiative launched at the Farm Hub in April. The project is a collaboration between the Farm Hub and Perlut, a professor at the University of New England who has studied Bobolinks for the past 20 years. He is also a member of the Farm Hub’s Applied Farmscape Ecology Research Collaborative, a group of researchers and scientists who focus on studying the connections between farming and ecology. The Farm Hub’s Farmscape Ecology program is keen on learning more about the local Bobolink population on the farm in order to manage the farmland for both humans and wildlife.

Perlut deployed geolocators and satellite tags to track the migration and movements of Bobolinks captured at the Farm Hub. The geolocater allow him to track the birds’ movements around the world, identifying their location with an accuracy of 50 kilometers. The devices store the data and he has to recapture these individuals next summer in order to retrieve the tag. The satellite tags are cutting edge technology that allow tracking in real time, identifying the bird’s location with an accuracy of up to within 250 meters. He is comparing birds from the Farm Hub with birds that he tracked from Shelburne Farms in Vermont. They caught six Bobolinks–five male and one female—at the Farm Hub. They also banded three Savannah Sparrows.

The palm-sized songbirds are distinct with their flat heads, spiky tails and dramatic aerial displays. In early Fall, from the northeastern U.S. and Canada, they head to Venezuela for a month, fly over the Amazon and land in Bolivia for a month, and then disperse to Argentina and Paraguay for the remainder of winter. This migration is driven by their search for food.

The current research goals are twofold: describe and compare the movement of Bobolinks at the Farm Hub with existing data from birds that breed in Vermont and explore their movements to nearby properties/farms and with other populations of Bobolinks. Perlut hopes to provide farmers in the region with the data that can help them balance their production needs with bird’s needs. Perlut noted, “These birds nest in hayfields so their reproductive success is really linked to the timing of which those hayfields are mowed. We will try to better understand what habitats they are using on and around the Farm Hub, particularly relative to when those fields are mowed.”

In the 2022 summer, Perlut and his crew will search for the birds they banded in 2021 to better understand if birds that bred there survive and return to the Farm Hub, and if birds hatched locally return to breed on the field where they hatched (as is the case in Vermont).

Capturing Bobolinks

The May visit was fruitful for Perlut and his team of student researchers—a windfall of six Bobolinks in a matter of hours. This was not as simple as it sounds. It took an extraordinary amount of patience to untangle a Bobolink from a net.

After rapidly retrieving them from mist net to cloth bag, the team worked in tandem to tag the birds. They took a blood sample, measured their wing span and beak length, and weighed them. Perlut banded them with three color bands and one numbered metal band. These bands allow anyone with keen binoculars to identify each bird as individuals. Finally, the crew attached a tracking device, much like wearing a backpack. Four of the birds wore satellite tags that transmit the birds position to the Argos satellite system, enabling us to follow their movements in real time. Two of the birds wore geolocators, which collect and store light level and temperature data. Perlut said he would try to retrieve these geolocators next summer to assess their migration.

How it started

Perlut, now based in southern Maine, first began researching Bobolinks as a PhD student at the University of Vermont.

“This project started as my Ph.D. work and continued well past that…I was brought on to start that project in Vermont to understand the relationship between mowing and grazing relative to the birds’ (Bobolinks) reproductive success, and then the project has gone way beyond that goal mostly because of advances in tracking and molecular technology,” Perlut says. His lab focuses on tracking the birds and following their local and international migration patterns to better understand the kind of habitats they are drawn to, related these movements to what they experience on the breeding grounds. Over the course of his career, he has captured more than 4,000 Bobolinks.

Ultimately the goal is to bring knowledge to farmers and landowners so they can balance production and management goals with bird needs.

“We want to see if we can find a balance that everyone gets to meet their objectives. My experience shows that farmers are more likely to adopt creative management strategies when they know more about the individual birds that they steward in their fields,” he says.

He also enjoys sharing his knowledge and passion with the next generation. For the research project at the Farm Hub the research team included two undergraduate students from the University of New England.

Full circle

Since the Bobolinks were tagged in May, Perlut and his research assistants have returned to the Farm Hub to monitor the tagged birds and look for nests. During a visit they discovered four Bobolink nests and banded 14 chicks, with the goal of seeing whether the birds that hatch on the Farm Hub return next year to breed at the farm. These nests are a hallmark of sorts, as the represent early positive returns of restoring grassland to the farm.

The team also learned that among the four satellite tags deployed, three had a software bug that caused them to malfunction after a few weeks. The good news is that the fourth satellite tag is functioning and has allowed them to track a Bobolink into its migration.

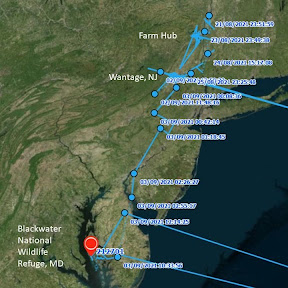

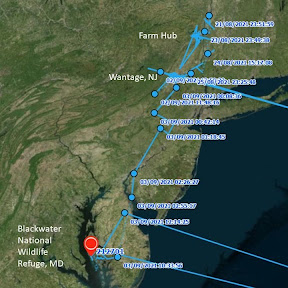

“The data has been truly amazing,” Perlut says. As of mid-August, the Bobolink had traveled roughly 70 miles south from the Farm Hub to Wantage, NJ where it spent a week on various farms before flying directly to the Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge in Maryland in early-September. As of late September, it had left Cuba and was crossing the Atlantic Ocean.

“These are tiny birds—the weight of two strawberries—and it is incredibly new to be able to track the real time movements with such precision,” he says of the satellite tags.

Despite twenty plus years of studying Bobolinks, Perlut never stops marveling at them. These tiny birds fuel themselves up on a diet of seeds and insects for a long journey. The Bobolink is in conserved tidal marsh “eating and eating to get fat and to have enough fuel to go on a super long flight,” he says. “It will add about fifty percent of its body weight before it tried to fly over the open ocean.”

– Amy Wu

In October, “The Wonder of the Bobolink” screened at the Princeton Environmental Film Festival, and it has been selected to screen at the Nature Without Borders International Film Festival and at the Wild and Scenic Film Festival 2022.

Siguiendo la migración y los movimientos de los pájaros cantores de prado, entre el Valle del Hudson, NY y América del Sur

Noah Perlut y sus asistentes de investigación universitarios llegaron a la granja al amanecer. El aire frío se llenó del sonido de sus pisadas en botas de goma al entrar en el pasto alto. Llevaban con sí muchas cosas–una caja de herramientas repleta de reglas, anillos de colores para poner en las patas de las aves, dispositivos de localización en miniatura, redes de niebla para atrapar pájaros, y bolsas de tela del tamaño de la palma de la mano para guardar a los pájaros. Horas antes del amanecer ya estaban preparados para atrapar a los tordos arroceros. Esto fue a principios de mayo.

La iniciativa de investigación sobre los tordos arroceros en el Farm Hub se inició en abril. El proyecto es una colaboración entre el Farm Hub y Perlut, un profesor en la University of New England que lleva 20 años estudiando el tordo arrocero. También es miembro del Applied Farmscape Ecology Research Collaborative del Farm Hub, un grupo de investigadores y científicos que estudian las conexiones entre la agricultura y la ecología. El programa de Farmscape Ecology del Farm Hub tiene un gran interés en aprender más acerca de la población local de tordos arroceros en el rancho, para gestionar las tierras de modo que beneficie a los humanos y a la vida silvestre.

Perlut utilizó geolocalizadores y etiquetas de satélite para rastrear la migración y los movimientos de los tordos arroceros capturados en el Farm Hub. Los geolocalizadores permiten seguir los movimientos de los pájaros por todo el mundo, identificando su posición con una precisión de 50 kilómetros. Los dispositivos almacenan los datos y Perlut deberá volver a capturar a estos mismos especímenes el próximo verano para recuperar la etiqueta. Las etiquetas satélite son tecnología de vanguardia que permiten rastrear al ave en tiempo real e identificar su posición con una precisión de hasta 250 metros. Perlut está comparando los pájaros del Farm Hub con los que ha rastreado de Shelburne Farms en Vermont. Capturaron seis tordos arroceros—cinco machos y una hembra—en el Farm Hub. También anillaron tres gorriones sabaneros (Passerculus sandwichensis).

Estos pájaros cantores del tamaño de la palma de la mano se distinguen por sus cabezas planas, colas con plumas aguzadas y exhibiciones aéreas espectaculares. A principios del otoño, desde el noreste de U. S. y Canadá, se dirigen a Venezuela por un mes, sobrevuelan el Amazonas y aterrizan en Bolivia durante otro mes, y luego se dispersan por Argentina y Paraguay durante el resto del invierno. La búsqueda de alimentos motiva esta migración.

Esta investigación tiene dos objetivos principales: describir el movimiento de los tordos arroceros del Farm Hub y compararlo con los datos existentes de las aves que se reproducen en Vermont y explorar sus movimientos a propiedades/granjas cercanas y con otras poblaciones de tordos arroceros. Perlut espera proporcionar a los agricultores de la región los datos que puedan ayudarles a equilibrar sus necesidades de producción con las necesidades de las aves. Perlut observa, “Estas aves anidan en los pastizales, por lo que su éxito reproductivo está realmente relacionado con el momento en que se siegan esos pastos. Trataremos de comprender mejor qué hábitats utilizan en el Farm Hub y las áreas cercanas, particularmente en relación con cuando se siegan esos campos”.

En el verano de 2022, Perlut y su equipo buscarán las aves que anillaron en 2021 para comprender mejor si las aves que se criaron en el Farm Hub sobreviven y regresan, y si las aves que nacieron aquí regresan a reproducirse en el mismo campo donde nacieron (tal como es el caso en Vermont).

Captura de tordos arroceros

La visita de Perlut y su equipo de estudiantes investigadores en mayo tuvo buenos resultados—capturaron seis tordos arroceros en cuestión de horas. Esto no fue tan fácil como parece. Se necesita muchísima paciencia para desenredar a un tordo arrocero de una red.

Después de soltarlos enseguida de la red de niebla y pasarlos a la bolsa de tela, el equipo colaboró en etiquetar a los pájaros. Tomaron una muestra de sangre, midieron la envergadura de las alas y la longitud del pico, y los pesaron. Perlut les puso tres anillos de colores y un anillo de metal numerado. Con estos anillos, cualquier persona con unos buenos binoculares puede identificar a cada ave individual. Finalmente, el equipo les puso un dispositivo de rastreo, como una mochila para el pájaro. Cuatro de las aves llevaban etiquetas de satélite que transmiten su posición al Sistema de Satélite Argos, por el que podemos seguir sus movimientos en tiempo real. Dos de los pájaros llevaban geolocalizadores, que miden y almacenan datos del nivel de luz y temperatura. Perlut dijo que intentaría recuperar estos geolocalizadores el próximo verano para estudiar su migración.

Cómo empezó

Perlut, actualmente basado en el sur de Maine, empezó a investigar el tordo arrocero durante sus estudios doctorales en University of Vermont.

“Este proyecto ha continuado mucho más allá de lo que yo habría imaginado… Empezó al iniciar ese proyecto en Vermont para comprender el efecto de la siega y el pastoreo en relación con el éxito reproductivo de los tordos arroceros, y luego el proyecto ha llegado mucho más allá de ese objetivo, principalmente debido a los avances en el rastreo y la tecnología molecular”, dice Perlut. Su laboratorio se concentra en rastrear a las aves y estudiar sus patrones de migración locales e internacionales para comprender mejor el tipo de hábitats que les atraen, y relacionar estos movimientos con lo que experimentan en los criaderos. A lo largo de su carrera ha capturado más de 4.000 tordos arroceros.

En fin, el objetivo es proporcionar a los agricultores información que pueda ayudarles a equilibrar sus necesidades de producción con las necesidades de las aves.

“Queremos ver si podemos encontrar un equilibrio en el que todos puedan lograr sus objetivos. Mi experiencia ha sido que los agricultores son más propensos a adoptar estrategias de manejo creativas cuando saben más sobre las aves individuales que habitan en sus campos”, dice.

También le gusta compartir su conocimiento y pasión con la próxima generación. Para el proyecto de investigación en el Farm Hub, el equipo de investigación incluyó a dos estudiantes de universitarios de University of New England.

El ciclo completo

Desde que etiquetaron a los tordos arroceros en mayo, Perlut y sus asistentes de investigación han regresado al Farm Hub para monitorear a los pájaros etiquetados y buscar nidos. Durante una visita, descubrieron cuatro nidos de tordo arrocero y anillaron a 14 crías, con el objetivo de ver si las aves criadas en el Farm Hub regresan al año siguiente para reproducirse en la granja. Estos nidos de por sí son una especie de victoria, ya que representan los primeros resultados positivos de restaurar los pastizales en la granja.

El equipo también se enteró de que, de las cuatro etiquetas de satélite utilizadas, tres tenían un error de software que causó su mal funcionamiento después de unas semanas. La buena noticia es que la cuarta etiqueta de satélite está funcionando bien y les ha permitido rastrear a un tordo arrocero en su migración.

“Los datos han sido realmente asombrosos”, dice Perlut. A mediados de agosto, el tordo arrocero había viajado aproximadamente 70 millas hacia el sur, del Farm Hub a Wantage, NJ donde pasó una semana en varias granjas antes de volar directamente a Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge en Maryland a principios de septiembre. A finales de septiembre, había salido de Cuba y estaba cruzando el Océano Atlántico.

“Estos pájaros son diminutos—del peso de dos fresas—y es increíblemente nuevo poder rastrear sus movimientos en tiempo real con tanta precisión”, dice de las etiquetas satélite.

Aunque lleva más de veinte años estudiando el tordo arrocero, Perlut nunca deja de maravillarse con ellos. Estos pequeños pájaros se nutren de una dieta de semillas e insectos para un largo viaje. El tordo arrocero permanece en las zonas conservadas de marisma pantanosa “comiendo y comiendo para engordarse y tener suficiente energía para hacer un vuelo súper largo”, dice. “Aumentará su peso por alrededor de un cincuenta por ciento antes de intentar sobrevolar el océano abierto”.

– Amy Wu