Connecting with the Art of Winslow Homer

The Hudson Valley has long attracted artists from New York City seeking inspiration from the region’s mountains and forests, rivers and waterfalls, sunsets, farmscapes, and vernacular architecture, as well as from the people who have lived here. Most famously, the 19th Century Hudson River School painters’ romantic relationship with the region has been widely documented and exhibited around the world.

Here in Ulster County, it’s been a not-so-well-kept secret amongst local art and history buffs that one of America’s greatest painters and illustrators, Winslow Homer, spent summers in Hurley in the 1870s. And many have heard that one of his more famous paintings, Snap the Whip (Metropolitan Museum of Art) completed in 1872, was based on the one-room schoolhouse on Hurley Mountain Road – just up the road and across from the Farm Hub.

By the 1870s Homer had moved from his hometown of Boston to New York City, where he became a member of the distinguished National Academy of Design and established his career as an artist and illustrator. After the Civil War, which he covered as an artist-correspondent, Homer began taking trips out of the city for exposure to the rural scenery and Americana that informed his art. He went often to New Jersey and Massachusetts, and to Saratoga and the Hudson Valley. His visits to Hurley took place roughly between 1871 and 1877. This predated his many sojourns to Canada, the Adirondacks, and the Caribbean, and his eventual move to the coast of Maine, where he would produce the paintings and watercolors that became his strongest legacy.

Thanks to the Hurley Heritage Society, Winslow Homer’s relationship to Hurley can now be understood right here on Main Street in an exhibition entitled “Homer’s Hurley: An Artist’s View.” The show, which is based on research done by members of the Heritage Society with art historian Reilly Rhodes for his 2017 book on Homer, displays reproductions of paintings and original engravings, cleverly arranged against the constraints of the Society’s small historic interior. In this way, we are introduced to Homer’s time here and his view of American pastoral life.

Exhibition curator Gail Whistance worked with a museum committee of local residents to include photos of Hurley landmarks and examples of objects that appear in the paintings. A slat-back chair, a child’s chalkboard, an artists’ easel – these connect the artist to specific sites and help us conjure the environment that Homer witnessed so long ago. Images of women on porches, children in school, and views across fields are evocative of the old farmhouses and scenes that we know today.

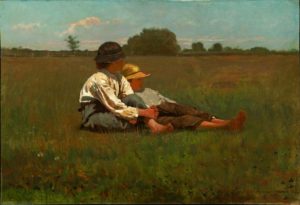

Much has changed since the 19th century. But for those of us who spend time regularly on the Hurley Flats, there is a look and a feeling to the artworks that is surprisingly familiar. The clothes have changed, as have the interiors, but the views through the windows perhaps not so much. In The Dinner Horn (Detroit Institute of Arts, 1873), for example, an open door shows the distant landscape and creates a painting within the painting. At the Farm Hub, when one looks through the end of the greenhouse, out the office window, or through an opening between two farm buildings, these square spaces similarly frame sky and fields – whether covered in snow in winter or crops in summer – in horizontal layers. It is believed that the painting Boys in a Pasture (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1874) was painted in Hurley, and we can easily see why in the flat field, the trees on the horizon, and the clouds floating low across the sky. Most of us in the 21st century don’t typically lie around in the fields on summer days, but if we did it might just look and feel a lot like this.

Today, of course, glancing across the Hurley Flats one is more likely to see farm buildings and tractors in motion than a couple of boys resting in the grass. What, then, is there to connect us with a New England-born artist from another century? Maybe it’s the belief that our landscape, no matter what the time period, is culturally meaningful. Or it could also be the tension inherent in knowing that people – across time and in spite of differences – are both interconnected and alone. Snap the Whip is said to be one of the last of Homer’s paintings that depicts a group of people in activity together. The boys are contending with the push and pull of freedom and restriction, indoors and outdoors, engaging together on a human chain and tumbling away alone. Aren’t we all?

The Farm Hub is an organization looking towards the future and striving to make change in broad strokes, and as such we who work there may not always make time for the intimate, or for yesterday’s news. But the fields are green, the clouds dramatic, the creek flanked with trees in the distance, and the light – when the sun goes over the cliff on the other side of the road – unmistakably Hurley. One can’t help but wonder what artists will see one hundred and fifty years from now.

“Homer’s Hurley” is no blockbuster at a major museum. The oil paintings are facsimiles, there’s no museum café and no visitor apps. But there’s something extraordinary about the well-researched history and the placement of images and objects brought together and interpreted by people who live here – some even in houses where Homer may have sketched. The display has a personal spirit you won’t get when visiting Homer’s originals at, say, the Met or the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. By all means, go there too, but – closer to home – enjoy learning about this artist in a building that was already old during his time, and through the lens of people who are deeply connected to this place.

— Brooke Pickering-Cole, Director