Thank you so much to all the hardworking students of Pine Bush middle and high school and Cornell Cooperative Extension Orange County who volunteered to harvest blueberries yesterday at the Farm Hub! These organic blueberries are being donated to local food pantries, shelters, and soup kitchens. There are a lot more blueberries to harvest, so if you’re interested, please join us! Volunteer […]

Continue readingFarm Hub Hosts Garlic Twilight

In the spirit of the garlic harvest season, Cornell Cooperative Extension (CCE) Vegetable Specialists Crystal Stewart, Teresa Rusinek, and Ethan Grundberg co-hosted an in-field garlic twilight meeting at the Farm Hub. The group presented on fusarium control methods and on effective weed suppression and mulching methods, including black plastic and while plastic mulches compared to straw and bare ground. Thank you to all the garlic growers that attended! To view more photos of the event, please click here.

Reducing Pest Populations with an Integrated Pest Management Strategy

Farmscape Ecology Coordinator Anne Bloomfield releases 60,000 Trichogramma wasps into the corn field to help reduce the European corn borer population, a common pest in the region that can do significant damage to corn. The release of these wasps is part of the Farm Hub’s Integrated Pest Management strategy.

Language Justice: Hearing All Voices at the Farm Hub

(Spanish translation to follow/traducción en español abajo)

On a cold yet bright mid-winter day, members of the Hudson Valley Farm Hub’s language justice team gathered in the farm’s classroom to discuss efforts to democratize language within the organization and, by extension, shift the team dynamics on the farm. The panelists were:

- Caitlin- Manager, Organizational Culture and Team Development

- Eustacio- Vegetable Team Member

- Jen- Community Relations Assistant

- Jesus- ProFarmer Trainee

- Pancho- Social and Racial Justice consultant, PazyPuente LLC

- Raul- Post-Harvest Coordinator

- Rosa- Vegetable Production Assistant

Three of the team members—Raul, Rosa, and Jesus—alternated taking on the role of interpreter (Spanish to English and English to Spanish). To begin, everyone tested their interpretation equipment (an ear piece and a small black receiver with channels and volume control) to ensure equal understanding and access to participation for all monolingual speakers, demonstrating what has become standard practice for meetings on the farm.

The Origins of Language Justice at the Farm Hub

“This all started in October 2015,” says Caitlin, the manager for Organizational Culture and Team Development at the Farm Hub. “We were working on long-term planning for the farm, and we were not able to engage the voices of all the staff members on account of the language barrier.” The Farm Hub hired social justice consultant Pancho to help them facilitate the organization’s transition toward a more inclusive and participatory culture. It was Pancho who first introduced the concept of language justice.

Pancho views expression of and access to language and culture as basic human rights that are often denied to non-English speakers in the United States. “Language is one of the key aspects in which we express our humanity,” he says. “So language justice is this notion of acknowledging and engaging in the whole humanity of those we work with.”

Pancho notes that introducing the concept of language justice at the Farm Hub was easier than in most places because the principles aligned with the organization’s existing mission, which focuses heavily on promoting equity and resilience. Still, the process of shifting the group’s mentality and priorities and making the logistical accommodations was not without its challenges.

“When we first started doing this language justice approach at the Farm Hub, it wasn’t at the top of everyone’s mind,” Raul says. “People needed interpretation, but it wasn’t easy for the whole organization to take the time to consider the steps it takes to make that happen.” He recalls interpreting for important events with little or no time to prepare, and even meetings where conversation was interpreted still only had written materials available in English. “[The process] was inconsistent at first,” he says. “So we couldn’t always get the information across to the people who needed to know what was happening.”

Pancho attributes this slow start to ingrained habit and under-examined privilege. “There is a personal inertia we all have, which is that it takes time for us to change. But then there is also an institutional and social inertia in which privilege, in this case language privilege, keeps reproducing itself,” he explains. “That’s why it too often becomes an afterthought. If I benefit from privilege, it’s very easy for me to forget about the needs and situations of those who don’t have it.”

A Multi-Pronged Approach

In the two years since the Farm Hub initiated its language justice efforts, the organization has taken many steps to break through the inertia. The entire staff now embraces the concept.

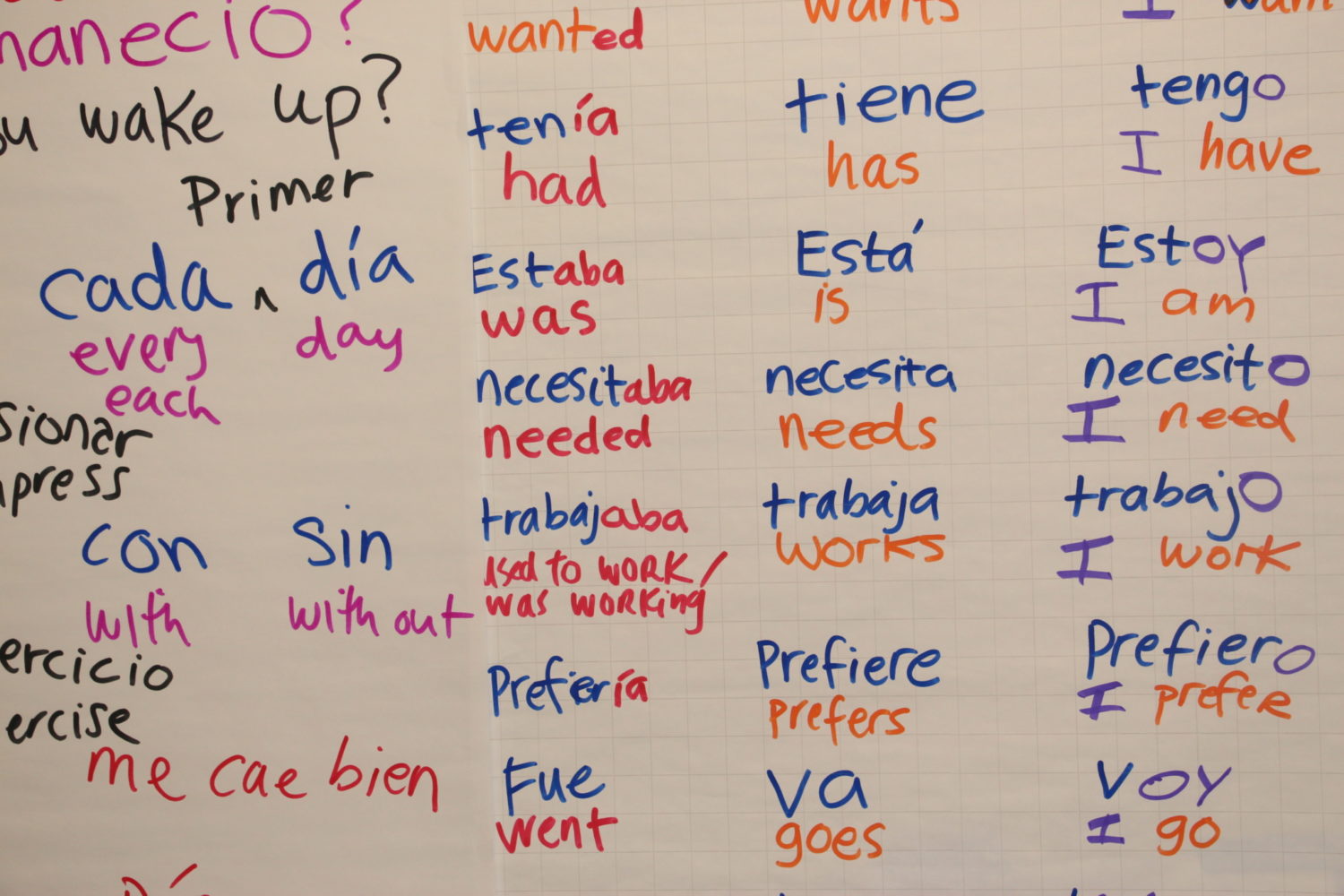

The organization has invested in simultaneous interpretation equipment and organized ongoing language classes for English and Spanish learners. Caracol Language Cooperative, a worker-owned cooperative that seeks to “create inclusive multilingual spaces where each of us may feel free to bring our whole self into the room,” has been instrumental in the Farm Hub’s adoption of language justice. The Farm Hub has worked with Caracol in multiple capacities, engaging them to facilitate interpretation training for bilingual staff members, hiring their interpreters for some all-staff events, and exploring ways to partner on language justice projects outside of the Farm Hub.

The all-team morning meetings on the farm include interpretation, reinforcing the importance of language justice on a daily basis. “Now, people that usually wouldn’t have the opportunity to share their ideas about something on the farm are able to do that because of the interpretation,” says Jesus. “That leads to leadership.”

Eustacio immigrated from Mexico in 2008. “When I first arrived, I understood absolutely no English,” he says in Spanish. For the past three years, Eustacio has been taking English classes through the Farm Hub. “At first I was nervous. I didn’t know how to say what I wanted, and I was ashamed of how I spoke. But over the course of time, I learned a little bit more and then by leaps and bounds,” he says.

In the past, Eustacio had to ask family members or coworkers to inform the office if he needed to take a sick day, but now he does that himself. He has also been able to get to know his English-speaking coworkers better. “I am very friendly and personable, and now I can communicate with everyone and chat for a while in English,” he says. “These are great experiences for me, and I am very proud of myself because I am advancing.” His English language skills have also expanded his employment opportunities; during the off-season, he now works at a bakery in Kingston.

For Rosa, language justice is about family and the preservation of culture. “It’s really important for Hispanic parents who have kids to talk to them in both languages, English and Spanish,” she says. “I know a lot of Hispanic kids that don’t know how to speak Spanish. They have family in Mexico, grandparents or cousins, and it’s really hard to communicate because the kids don’t understand.”

Practice Makes Perfect

In 2017, the language team began holding weekly practice interpretation sessions to sharpen their skills. “One of the concepts of language justice is to make sure that everybody’s voice is heard and everybody can share what they know. We practice that in a smaller group,” Raul explains. Participants often practice interpretation using stories from their own lives, creating the added benefit of team members getting to know one another better.

“We’ve been able to really bond around these practices,” Raul says. “That’s what language justice tries to do overall: to allow everyone to hear each other and to bond. So these sessions have been great for us.”

Language Justice Milestones

In 2016, the Farm Hub launched the Native American Seed Sanctuary in collaboration with the Seedshed and the Akwesasne Mohawk tribe. The main goals include growing native seed varieties and helping to preserve indigenous seed sovereignty and culture.

Over the past two years, the Farm Hub staff and members of the Akwesasne tribe have come together for various ceremonies, such as the harvest celebration. At these events, three languages are spoken: Mohawk, Spanish, and English. The Mohawk perform the ceremonies in their native language, then interpret into English themselves, after which the Farm Hub’s language justice team interprets in Spanish. “It’s actually very deep and powerful, and it captures language justice,” says Raul, pointing out that both English and Spanish are languages only spoken on this continent after colonization. “When they do the ceremonies in their native language, it is hearing one of the true languages of this land.”

Leveling the (Playing) Field

One of the most powerful impacts of the language justice work at the Farm Hub has been to increase the opportunities for Spanish speakers to share their expertise and leadership skills.

“I’ve been here three years and a part of this team since it began,” Raul says. “It has made it possible for Eustacio to lead classes in cooking or in baking foods that are based on our cultural values. So Eustacio has become a teacher to a lot of English speakers, showing them how to do so many things that we do back home.”

Jesus recalls witnessing a similar dynamic in the staff community garden: “When the garden first started, we were making raised beds. I saw that Victor, one of the vegetable team members who doesn’t fully speak English, was able to help Caitlin make her raised bed, speaking in English and Caitlin in Spanish too.”

The bilingual learning has also increased camaraderie and communication in day-to-day farming activities. The Farm Hub’s farmer trainees (ProFarmers) and other staff have also been learning Spanish, so the effort to communicate goes both ways. “Before, Spanish speakers wouldn’t talk much in the field,” Rosa says. “But now that there have been all these English and Spanish classes, everyone is trying to talk to each other—in English and in Spanish.” Jesus adds, “I don’t see any shame or embarrassment. It’s been great here in this environment. It’s not just about working together, but being a community, being friends with each other.”

Adelante!

“To me, language justice has been one of the tools that this organization has used to close the unintentional segregation that we used to have,” Raul says. “It used to be all-white office folk who had very little interaction with the people of color staff who worked in the field. Now people can actually interact with one another, and it doesn’t feel like two separate teams who work for the same organization. It feels like we’re one team learning together.”

But the work is by no means done. Creating equality around language is an uphill battle against the predominant culture of segregation and privilege for native English speakers in society at large. “It is in the beginning stages,” says Jen, Community Relations assistant. “But, at the very least, it elevates our expectations of ourselves and our organization, which not only brings a sense of willingness but also enthusiasm to continue the work.”

All of these language justice efforts must be made in the midst of running an active production farm. “The crops don’t stop needing you in the height of the summer,” Salemi says. “The commitment is there, but it is slow work. And sometimes we don’t see where we should be pushing more, and we’re perhaps resting a bit. But we know this is just the beginning of the journey.”

According to the US Department of Labor’s National Agricultural Workers Survey (NAWS), of the estimated 2.5 million farm workers in the country, 71 percent are immigrants, with 70 percent reporting Spanish as their dominant language. Salemi continues, “Through our language justice work, the experiences that we bring from our own lives and the trust that we’re building with each other will continue to support our organizational transformation and, hopefully, enable us to share what we’re learning with the community beyond the Farm Hub.”

En Español:

Justicia del Lenguaje: Escuchando todas las voces en Farm Hub

En una tarde fría pero soleada de un día de invierno, miembros del equipo de justicia de lenguaje de Hudson Valley Farm Hub se juntaron en el salón de clases de la granja para discutir los esfuerzos internos de la organización para democratizar el lenguaje y como resultado, cambiar las dinámicas del equipo. Las personas que estuvieron en el panel fueron:

- Caitlin- Gerente de Cultura Organizacional y Desarrollo Profesional del equipo

- Eustacio- Miembro del equipo de vegetales

- Jen- Asistente de relaciones comunitarias

- Jesús- Alumno de ProFarmer

- Pancho- Consultor de Justicia social y racial, PazyPuente LLC

- Raúl- Coordinador Pos cosecha

- Rosa- Asistente de producción de vegetales

Tres personas del equipo—Raúl, Rosa y Jesús— se turnaron interpretando (español a inglés e inglés a español) Para empezar, toda persona probó su equipo de interpretación (un audífono y una radio negra pequeña con canales y control de volumen) para cerciorarse de que hay entendimiento y participación para las personas monolingües. Demostrando lo que se ha vuelto una práctica estándar en las reuniones en la granja.

Los orígenes de la Justicia del Lenguaje en Farm Hub

“Todo esto empezó el 15 de octubre del 2015,” dice Caitlin, la gerente de Cultura organizacional y desarrollo profesional del equipo de Farm Hub. “Estábamos trabajando en la planificación a largo plazo para la granja, y no pudimos involucrar todas las voces del personal debido a las barreras del idioma.” Farm Hub contrató al consultor de justicia social Pancho para ayudar en la transición hacia una cultura de mayor inclusión y participación. Fue Pancho que nos introdujo al concepto de justicia de lenguaje.

Las perspectivas y expresiones de Pancho sobre el acceso al lenguaje y la cultura las definen como derechos humanos básicos que a menudo se les niegan a las personas que no hablan inglés en los Estados Unidos. “El lenguaje es uno de los aspectos claves de la expresión de nuestra humanidad,” dice él. Entonces la justicia del lenguaje es esta noción de reconocer y comprometerse a involucrar en su humanidad entera a las personas con las que trabajamos.”

Pancho resalta que el incorporar el concepto de justicia de lenguaje en Farm Hub fue más fácil que en otros lugares porque los principios se alinean con la misión existente de la organización, que se enfoca considerablemente en promover la equidad y la resiliencia. Sin embargo, el proceso de cambio de mentalidad y prioridades del grupo y ejecución de la logística necesaria no ocurrió sin encontrar retos.

“Cuando empezamos a llevar a cabo el enfoque de justicia de lenguaje en Farm Hub, no estaba en la mente de toda la gente.” dice Raúl. “La gente necesitaba interpretación, pero no era fácil para toda la organización dedicar el tiempo para considerar los pasos que se necesitan para que eso ocurra.” El se acuerda que interpretó para eventos importantes con nada o poco tiempo de preparación, e incluso en reuniones en las que se ofrecía interpretación, solo se tenían materiales en inglés escritos a mano. “[El proceso] no era consistente al principio,” dice él. “Entonces no siempre podíamos hacer que la información llegue a toda persona que necesitaba saber lo que estaba pasando.”

Pancho atribuye este comienzo lento al hábito enraizado de no ser conscientes del privilegio que se tiene. “Hay una inercia personal que toda persona tiene, que es la que nos hace tardar en en cambiar. Pero también hay una inercia social e institucional en la que el privilegio, en este caso el privilegio del lenguaje se autorreproduce” explica. “Es por esto que, a menudo, es algo que no se piensa hasta el final. Si me beneficio del privilegio, es fácil para mí olvidarme de las necesidades y situaciones de los que no lo tienen.”

Un enfoque multifacético

Desde hace dos años que Farm Hub inició sus esfuerzos por la justicia del lenguaje la organización ha llevado a cabo varios pasos para romper la inercia. Ahora todo el personal adopta el concepto.

La organización ha invertido en la compra de equipo de interpretación simultánea y ha organizado clases regularmente para aprendizaje del inglés y el español. La Cooperativa de Lenguaje Caracol, una cooperativa de trabajo que busca “crear espacios multilingües inclusivos donde cada persona pueda sentir la libertad de traer todo su ser a la participación,” ha sido instrumental en la adopción de justicia de lenguaje en Farm Hub. Farm Hub ha trabajado con Caracol en diferentes capacidades, involucrándoles en la facilitación de entrenamientos en interpretación para el personal bilingüe, contratando sus intérpretes para algunos eventos de todo el personal, y explorando maneras para colaborar en proyectos de justicia del lenguaje fuera de Farm Hub.

Las reuniones de todo el equipo de finca en las mañanas incluyen interpretación, fortaleciendo la importancia de la justicia del lenguaje en el día a día. “Ahora las personas que usualmente no hubiesen tenido la oportunidad de compartir sus ideas sobre algo de la granja pueden hacerlo gracias a la interpretación,” dice Jesús. “Eso lleva al liderazgo.”

Eustacio migró desde México en el 2008. “Cuando llegué no entendía absolutamente nada de inglés,” dice en español. Durante los últimos tres años, Eustacio ha estudiado en clases de inglés en Farm Hub. Al principio me sentía nervioso. No sabía como decir lo que quería, y me daba vergüenza la manera en la que yo hablaba. Pero con el paso del tiempo, aprendí un poquito más, así a tumbos y saltos” dice.

Antes, Eustacio tenía que pedir a sus parientes o colegas que avisasen a la oficina que necesitaba un día de descanso por que estaba enfermo, pero ahora ya lo hace él mismo. También ha podido conocer mejor a sus colegas anglohablantes. “Soy una persona muy amistosa y amable, y ahora ya puedo comunicarme con toda persona y conversar un rato en inglés,” dice. “Estas experiencias son buenas para mí y estoy muy orgulloso de mí mismo porque estoy progresando.” Sus habilidades para hablar inglés también han expandido sus oportunidades laborales; fuera de la temporada agrícola ahora trabaja en una panadería en Kingston.

Para Rosa, la justicia del lenguaje tiene que ver con la familia y la preservación de la cultura. “Es muy importante para los padres hispanohablantes que tienen hijas e hijos el poder hablarles en ambos idiomas, inglés y español,” dice. “Yo conozco a muchos y muchas jóvenes hispanas que no saben hablar español. Tienen familia en México, abuelitos o primas/os, y es muy difícil comunicarse porque no entienden.”

La práctica hace la perfección

En el 2017, el equipo de lenguaje empezó a practicar semanalmente en sesiones de interpretación para mejorar sus habilidades. “Uno de los conceptos de la justicia del lenguaje es asegurarse de que todas las voces se escuchen y que puedan compartir sus conocimientos. Practicamos eso en un grupo pequeño,” Raúl explica. Las personas participantes practican interpretación utilizando historias de sus vidas, creando el beneficio de conocerse mejor.

“Hemos podido establecer lazos con esta práctica,” dice Raúl. “Sobre todo, eso es lo que trata de hacer la justicia del lenguaje: permitir que las personas se escuchen mutuamente y creen lazos. Entonces estas sesiones han sido magníficas para nosotras/os.”

Hitos de la justicia del lenguaje

En el 2016, Farm Hub lanzó el Santuario de semillas nativo-americanas en colaboración con Seedshed y la tribu Akwesasne Mohawk. Las metas principales incluyen sembrar una variedad de semillas nativas y ayudar a preservar la soberanía de las semillas indígenas y su cultura.

Durante los últimos dos años; el personal de Farm Hub y miembros de la tribu Akwesasne se han unido durante varias ceremonias, como la celebración de la cosecha. Durante estos eventos, se hablan tres idiomas: mohawk, español e inglés. La ceremonia mohawk es en su idioma nativo, que interpretan al inglés, y luego el equipo de justicia de lenguaje de Farm Hub lo interpreta al español. “Es muy profundo y poderoso, y plasma la justicia del lenguaje, “dice Raúl, señalando que ambos idiomas, inglés y español son idiomas que se hablan en el continente desde la colonización. “Cuando se hacen ceremonias en sus idiomas nativos, escuchamos uno de los lenguajes verdaderos de este territorio.”

Equilibrar el terreno de juego

Uno de los impactos más profundos del trabajo de justicia del lenguaje en Farm Hub ha sido incrementar las oportunidades de las personas hispanohablantes para compartir sus conocimientos y habilidades de liderazgo.

“He estado aquí tres años y parte de este equipo desde el principio,” dice Raúl. “Ha hecho posible que Eustacio lidere clases de cocina o repostería basadas en nuestros valores culturales. Eustacio se ha vuelto el maestro de bastantes anglohablantes, mostrándoles cómo hacer cosas como hacemos nosotros en nuestros hogares.”

Jesús recuerda ser testigo de una dinámica similar en el jardín comunitario del personal: “Cuando empezó el jardín, estábamos haciendo las camas elevadas de cultivos. Vi que Víctor, uno de los miembros del equipo de vegetales que no habla mucho inglés, pudo ayudar a Caitlin a hacer su cama elevada, hablando en inglés y Caitilin lo hizo en español.”

El aprendizaje bilingüe ha incrementado la camaradería y comunicación en las actividades del día a día en la granja. Los alumnos granjeros de Farm Hub (ProFarmers) y el personal han estado aprendiendo español, para que el esfuerzo de comunicarse sea recíproco. “Antes, los hispanohablantes no hablaban mucho en el campo,” Rosa dice. “Pero ahora que ha habido todas estas clases de inglés y español, toda persona está tratando de hablarse—en español e inglés. ” Jesús añade, “no veo vergüenza ni bochorno. Ha sido magnífico estar en este ambiente. No solo se trata de trabajar en equipo, pero de ser comunidad, hacer amistad.”

¡Adelante!

“Para mí la justicia del lenguaje ha sido una de las herramientas que esta organización ha utilizado para cerrar la segregación involuntaria que teníamos,” dice Raúl. “Era una oficina de solo gente blanca que tenía muy poca interacción con la gente no blanca que trabajaba en el campo. Ahora la gente interactúa entre sí, y no se siente como que hay dos equipos separados que trabajan para la misma organización. Se siente que somos un equipo unido.”

Pero el trabajo no termina ahí. Crear equidad del lenguaje es una batalla contra la corriente de la cultura predominante de segregación y privilegio para los anglohablantes a nivel más amplio de la sociedad. “Estamos en un nivel de inicio,” dice Jen, la asistente de relaciones comunitarias. “Pero, por lo menos, eleva nuestras expectativas sobre nosotras mismas y nuestra organización, lo que no solo da un sentido de voluntad sino también de entusiasmo para continuar con el trabajo.”

Todos estos esfuerzos de justicia de lenguaje deben de hacerse en un contexto de manejar una granja de producción activa. “Los cultivos no dejan de necesitarnos en la temporada de verano,” dice Caitlin. “El compromiso está ahí, pero es un trabajo lento. Y a veces no vemos dónde hacer más esfuerzo, y tal vez donde descansar un poco. Pero sabemos que estamos al inicio de el viaje.”

De acuerdo con la Encuesta Nacional de Trabajadores Agrícolas del Departamento de Trabajo de Estados Unidos (NAWS), del número estimado de 2.5 millones de trabajadores agrícolas en el país, 71 por ciento son inmigrantes, con un 70 por ciento que declara que el español es su idioma dominante. Caitlin continúa, “Gracias a nuestro trabajo de justicia del lenguaje, las experiencias que compartimos de nuestras propias vidas y la confianza que estamos creando entre nosotros continuará apoyando la transformación de nuestra organización y, ojalá nos permita compartir lo que estamos aprendiendo con la comunidad, más allá de Farm Hub.”

New Projects on the Horizon for ProFarmer Trainees

In the second year of the Farm Hub’s ProFarmer program, farmer trainees develop independent projects around one crop and within a specific area of interest. The purpose is to gain direct experience managing a crop organically, from start to finish, over a growing season. This year, ProFarmers are working with strawberries, squash, and hops—with support from staff and mentors. Each ProFarmer obtains and records data on their crop, creates and executes a crop plan, and manages the crop’s needs, applying the cultural practices they learned in the field during the first year.

Three of our 2018 ProFarmer projects are previewed below.

NAILAH MARIE ELLIS

Intercropping with Strawberries

Ellis will grow strawberries, one of the crops she envisions on her future farm. She will intercrop her strawberry planting, a practice farmers have utilized for many generations. One classic example of intercropping is the “Three Sisters” planting method, developed by Native Americans who planted corn, beans, and squash together.

By growing symbiotic crops in close proximity to one another, Ellis will introduce biological diversity into the system as a potential way to reduce pest and pathogen pressure on the strawberries, both as plants and fruits. On nearly a quarter of an acre of farmland, Ellis will intercrop half of the plot with flowers (e.g., marigolds) and culinary herbs (e.g, sage, thyme, caraway, borage), monitoring differences in pest and disease pressure between the two halves.

The goals of this project are twofold. First, this work explores the results of intercropping as a method of growing crops in a system of increased biodiversity. The second goal is to implement a roll and crimped system to reduce tillage and experiment with growing strawberries without plastic mulch (rolled rye is the primary mulch, supplemented as needed with alfalfa straw).

She will start planting in June and complete the harvest in October, with plans to overwinter the plants so they will produce strawberries again next year.

ANDREW CASNER

Winter Squash and Compost Teas

Casner’s project involves growing winter squash seed by experimenting with actively aerated compost tea. He is passionate about composting both to reduce waste and as a tool to contribute to soil and plant fertility. His work is inspired by the methods of Dr. Elaine Ingham (president and owner of Soil Foodweb), who pioneered this approach. This method is complex and requires a great deal of diligence and attention to detail.

In brief, the process starts with high quality compost containing diverse beneficial microorganisms. Casner takes a small amount of this compost and places it into a water filled tank attached to an aerator which bubbles oxygen into the water. After several hours, the bacteria, fungi, protozoa, and nematodes from the compost multiply in the “tea.”Casner applies this tea to the winter squash as it grows in the field throughout the season. This process builds up the crop’s health and ability to forage for nutrients from the soil in partnership with the life in the soil.

The aim is to assess the potential of this fertility program as a tool to improve the productivity and vitality of the soils using materials available to organic farmers. This spring, Casner established a compost pile to reduce waste at the farm and gain more experience with all aspects of the process, from organics recycling and compost production to compost tea brewing and field application.

JAYNE HENSON

Testing Hops Varieties

Henson’s project involves growing hops, which is increasingly of interest to regional growers as a result of the 2013 New York Farm Brewery Law. This piece of legislation incentivizes the use of New York grown products and the development of local businesses pertaining to the brewing industry.

Henson will establish a one-acre hop yard containing six different varieties of hops for medicinal and brewing purposes. Already familiar with growing grains from her experience growing up on a farm in Kansas, she plans to make hops part of her future farm operation.

Growing hops presents a variety of challenges for farmers in this region. The wet climate and consistent pest pressure can create significant problems that are further compounded by the additional challenges of growing organically. Henson will be using innovative techniques, including using cuttings from cover crops and transferring those onto the hop rows to provide nutrients and control weeds in a process known as “transfer mulching.” Other techniques include creating habitats for beneficial insects to control pests, as well as close monitoring of weather patterns in conjunction with applying organic fungicides.

She looks forward to collaborating and sharing ideas with local farmers, brewers and others in the community as the season progresses.

Kingston YMCA Farm Project

On Friday, April 13, the Farm Hub joined the YMCA Farm Project in Kingston for a volunteer work-day to help build greenhouse tables, prep the garden, and teach students how to use power tools. Together with the Farm Project’s education director, Susan Hereth, and eight student workers, the team pitched in to kick off the YMCA’s fifth growing season and support the organization’s vision to “grow a healthier Kingston.”

Sara Katz, education program manager at the Farm Hub, led a safety demonstration to instruct the student workers on the proper use of power tools. Putting these new skills into practice, student workers broke into groups of two to three and, with guidance from staff members, built several tables to be used for greenhouse seeding.

Other volunteers spread compost and wood chips in the grow beds to prepare for the transplanting process. “The students came in with different backgrounds and levels of experience,” Katz explained, “but all of them were enthusiastic to learn and develop their skills. Because of the range of tasks, everybody got to challenge themselves and try something new. They were then able to apply what they had learned immediately after the training.”

Located behind the YMCA in midtown Kingston, this educational urban farm is oriented toward youth development and allowing young people to learn about growing food by doing the work themselves and getting their hands dirty. Four youth programs, with participants ranging from preschoolers to high school students run throughout the year. The farm will soon pilot a bee pollinator habitat with SUNY New Paltz.

The guiding principles are twofold: giving youth an opportunity to develop valuable skills and contributing to the broader community’s wellbeing. The program offers a variety of experiences, from working on the farm and helping run the project’s farm stands in Kingston, to learning about food justice and how food systems operate. This type of hands-on participation complements the learning style offered in conventional classroom settings, with all of the young participants receiving an hourly wage and some receiving academic credit.

In keeping with the idea to provide the community with access to healthy, locally produced food, all of the YMCA Farm Project’s farm stands are centrally located for optimal accessibility. The locations are deliberately chosen to eliminate common barriers such as lack of transportation and to shift away from having farmers’ markets exclusively in high-income areas.

At the end of the day, the Farm Hub team said goodbye to the students and staff at the YMCA and made the short drive back to Hurley. Despite the proximity, it almost felt as though Kingston was an entirely different world. Perhaps that is part of what made it so memorable; the opportunity to bring some of the skills and practices that are usually associated with rural farming communities to an urban area.

“It was refreshing to get off the farm for a day,” said Katz. “Seeing how much the kids appreciated hands-on learning and the sense of accomplishment that came with seeing the fruits of their labor was fulfilling.”

For more information on the Kingston YMCA Farm Project, click here.

Seeds of Hope Premiere

On Wednesday, March 28, an enthusiastic audience of over 200 gathered at the Senate Garage in Kingston for the debut screening of “Seeds of Hope,” a short documentary that tells the story of a collaborative initiative to preserve Native American culture and foodways through seed saving at the Farm Hub. The project was formed in 2016 as a partnership between the Mohawk/Akwesasne tribe of northern New York State, the non-profit Seedshed, and the Farm Hub.

The film’s director, award winning filmmaker and environmentalist Jon Bowermaster, introduced the 24-minute documentary which features interviews as well as activities from planting to harvest, illuminating the beauty of the Hudson Valley season by season. A panel discussion with project participants followed the film screening, with Farm Hub Director, Brooke Pickering-Cole moderating the discussion and questions from the audience. Panelists included Ken Greene of Seedshed, Indigenous Seed Keeper and educator Rowen White, Karahkwino-Tina Square from the Native North American Travelling College, and Kenny Perkins of the Akwesasne Task Force on the Environment.

White spoke eloquently about the ways in which projects like the Seed Sanctuary can help address persistent issues caused by the loss of land and culture through “reconciling the intergenerational trauma…Not one person is untouched by the broken story with land and food and place.”

Panelists described youth programs at Akwesasne, where corn, beans, and squash grown at the Farm Hub and sent north are helping a new generation reconnect with food traditions and with Mohawk language, ceremonies, and songs associated with food. These efforts are helping young people “transcend the syndrome of not knowing who they are or where they came from.” After all, as White observed, “many are only one or two generations removed from the seed song carriers.”

“Seeds of Hope” accompanies two other films in a series produced by Bowermaster’s Oceans 8 Films entitled “Hope on the Hudson.” Click here to view the full calendar of screenings.

Visit our photo gallery for photos from the March 28th event.

Click here to view the Seeds of Hope trailer.

Event Invitation: Seeds of Hope

Seeds of Hope

Wednesday, March 28, 2018

The Senate Garage

4 N. Front St. Kingston

6:30 PM

Join the Hudson Valley Farm Hub, Seedshed, and Oceans 8 Films at the Senate Garage in Kingston, NY on March 28th at 6:30 PM for a screening of Seeds of Hope! This short documentary film tells the story of a collaborative initiative to preserve Native American culture and foodways through seed saving at the Hudson Valley Farm Hub. Seeds of Hope is created by award-winning filmmaker and environmentalist Jon Bowermaster as part of a series entitled “Hope on the Hudson.”

The film includes interviews with Akwesasne community members and others involved in the project, highlighting the 2017 Seed Sanctuary activities from planting to harvest, and illuminating the beauty of the Hudson Valley season by season.

Q&A to follow the film with members of the Akwesasne community and the filmmaker.

This event is free and open to the public.

Seating is limited and registration is encouraged. Sign up here!

ProFarmer Helps Farmers Rebuild in Puerto Rico

This past December, second year ProFarmer, Jayne Henson, traveled to Puerto Rico in the aftermath of the devastating hurricanes to help farmers rebuild and prepare for the challenges ahead. Below is a firsthand account of Jayne’s experience.

In early September 2017, Hurricane Irma hit the coast of Puerto Rico, leaving over one million people without electricity. Less than two weeks later, before the people affected by Irma even had a chance to start recovering, Hurricane Maria slammed into the island. Upon learning about the devastation in Puerto Rico, I immediately wanted to help. As part of the ProFarmer Training program at the Hudson Valley Farm Hub, I have learned to focus not only on the ins and outs of growing quality, healthy vegetables, but also on food justice and our role in the food system.

After reaching out to some of my friends from Puerto Rico I learned of an effort called “Guagua Solidaria,” or The Solidarity Van. This program is a grassroots coalition of folks who form “solidarity brigades” that travel to farms on Puerto Rico and help them rebuild. I was fortunate enough to get connected with this effort and was invited to the island as part of a brigade formed by members of the Queer Kitchen Brigade (QKB),” an organization started by Puerto Rican and Latinx New Yorkers who wanted to send healthy food to those devastated by the hurricanes.

The group began by pickling and canning fresh produce donated by New York farms and sending shipments to the island. They also organized pop-up canning classes and workshops to teach others in the community how to preserve fresh food while providing relief for people in Puerto Rico.

An Uneven Landscape

After landing in balmy San Juan and being picked up by my compatriots, we headed to our temporary base of operations. Driving through the streets was dizzying. From a cursory glance it seemed as though the island was back on its feet, as the airport and hotels on its outskirts appeared clean and full of electricity and life. However, it didn’t take long for that façade to fade.

The farther we got from the resort areas of San Juan, the more evident the extent of the devastation became. A quick 20-minute drive along the highway revealed fallen billboards and power lines and entire blocks of homes that once provided shelter and community now reduced to piles of splinters and sheets of tin. Low-income neighborhoods in states of devastation pockmarked the landscape of seemingly unaffected resort villas and luxury high rises.

This theme would carry out for the duration of our stay as we witnessed tourist-heavy areas receiving the utmost attention and access to amenities, while rural communities were barely hanging on through sheer force of will and community resiliency.

Bosque Del Monte Grande

Bosque Del Monte Grande, the first farm we visited, sits on about eight acres of land. Most of it is along a mountainside and at its highest point it flattens out into a one-acre garden with a small wooden structure that looks out over the mountainside and down to the sea. Its sole proprietor is a woman named Norycell, affectionately called Nory. From the moment I met her, it was clear that the heartbeat of her land, crops, and animals echoed in her pulse.

Nory raises a small herd of goats, two donkeys, and a newly formed flock of chickens. Along with her livestock she also raises perennial crops such as bananas and other fruits, as well as several annual crops, her specialty being okra. One evening, she revealed to me a canister of okra seeds that she had been painstakingly saving and selecting for resilience, removing plants that showed the slightest signs of weakness, and cultivating those that showed strength. It was clear to me that these seeds were her treasures.

The land that was once clear and vibrant with growing vegetables was now covered with fallen timber and debris. Our purpose was clear: we were there to help her take it back. Along with clearing the land, I was also assigned the task of building a compost sifter that Nory herself had designed.

Her farm exists as a place of community knowledge. She does not sell her produce at market but instead uses it to feed those that come to visit her farm, which serves as a place of education where she teaches others how to cultivate their own path to sustainability regardless of their financial status. She also works closely with NRCS on agro-forestry and sustainability programs, and she is an organic certifier for Puerto Rico. Her work is, in a word, inspiring.

Finca Flamboyant

After three days in Cabo Rojo we headed farther inland and higher into the mountains of Sabana Grande to our second farm of the trip, Finca Flamboyant, which describes itself as “A QTPOC-stewarded land project, artist retreat and home in the southwest mountains of Puerto Rico.” They are “a sanctuary for marginalized folks to spend time in, work on their art, learn/teach about farming and plant medicine, skill-share, or just come and take a break for healing and rejuvenation in a rural, tropical setting. … Recognizing the intersecting impact of racism, homophobia, and gender based violence, Finca Flamboyánt is specifically a project for and by Queer People of Color impacted by colonialism, displacement, and diaspora.”

La Finca sits atop a lush green mountain looking out onto rainforest valleys full of dew and mystery. As we drove up the mountainous roads, I was educated about some of the agricultural history of the area and how it was most widely used for its coffee production. Nearly vertical mountainsides were cleared, cultivated, and planted with coffee trees. Puerto Rico is full of the echoes of colonialism, and as we wound our way up the mountainside its impact reverberated in my head.

The effects of Maria were harsh on Finca Flamboyant. Grand structures and mango trees were demolished, covering ground that had once been vibrant and usable, and so we set about the familiar task of clearing downed trees. Much of the top soil had been washed away through erosion, so we took this opportunity to use the wood litter to build an erosion barrier to help prevent further breakdown. Once again, I was tasked with construction duties as we worked to create a “Vivero,” a tropical nursery or greenhouse used to shield young plants from the harsh sun and high temperatures. The roof also functioned as a rain catchment system. Seeing our structure standing tall atop the mountain and knowing that it would be used to bring new life to this farm and the people it cares for gave me great pride and joy.

Not The Freedom We Want, But The Freedom They Choose

Back in my San Juan hotel room as I took my first shower of the trip I felt the dirt, sweat, and tension of tired muscles wash from my body, now covered in bug bites and sunburns. I sat on the deck and listened to the waves wash onto shore. I thought about what Puerto Rico had given me, what I owed Puerto Rico. The things I will never be able to pay back. It is the responsibility of all of us who call ourselves Americans to protect and nurture these lands that were colonized, to do everything in our power to give them a voice, and grant them freedom. Not the freedom we want for them, but the freedom they choose.

-Jayne Henson

Farm Hub Seeks In-Field Education Manager

The Hudson Valley Farm Hub is now seeking to fill the full-time position of ProFarmer In-Field Education Manager. As a part of the leadership team at the Farm Hub, the In-Field Education Manager will be responsible for in-field instruction, mentoring, and the daily supervision of ProFarmer trainees, who are full-time, year-round Farm Hub employees. He/she will be instrumental in furthering the educational and ecological goals of the Farm Hub.

If you are interested in this position, please read the full job description.